The richest city in the world

Khaldoon Khalifa al Mubarak is a man in a hurry. The 31-year-old, American-educated developer steps on the gas of his silver Audi and zooms past a hole in the ground crawling with construction workers – the future home of a $1.3 billion complex featuring three skyscrapers, two five-star hotels, and a souk.

The car zips by a new $3 billion hotel that boasts 1,002 Swarovski crystal chandeliers and a gold-leaf dome larger than the one atop St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. In the distance, glittering in the aqua-blue Persian Gulf, are dozens of islands that will one day sprout skyscrapers, hotels, museums, hospitals, and factories financed in part by the government-owned investment company that Khaldoon runs, Mubadala Development. In all, plans call for almost $200 billion to be spent here over the next ten years.

A $6.8 billion airport expansion includes a runway wide enough to land Etihad Airways’ Airbus A380 jets.

“We move fast,” Khaldoon says, his crisp, white headscarf whipping in the wind. “Think about it: How many places in the world can you say, ‘I’m going to establish an airline,’ and boom, two years later you have 21 planes and 37 destinations? How many places in the world can you say, ‘I need 15,000 hotel rooms,’ and boom, you have 100 new hotels in the works? How many places can you say, ‘I want world-class hospitals, universities, and museums,’ and boom, the Sorbonne, Cleveland Clinic, Guggenheim, and Louvre are on the way?”

Welcome to Abu Dhabi, the capital of the United Arab Emirates and the richest city in the world. The emirate’s 420,000 citizens, who sit on one-tenth of the planet’s oil and have almost $1 trillion invested abroad, are worth about $17 million apiece. (A million foreign workers don’t share in the wealth.) Yet most people couldn’t find Abu Dhabi on a map. Khaldoon’s job is to change that. Tall, handsome, and politically savvy, he wants to make his hometown mentioned in the same breath as Singapore, Tokyo – and yes, Dubai.

But does the UAE, a federation of seven emirates strung out along the Persian Gulf, need another Dubai just a two-hour drive away? Does it need another long-haul airline, another financial center, another tourism destination, another billion-dollar hotel? “The short answer,” says Khaldoon, “is yes. But I don’t like to use comparisons with Dubai. We’re not trying to be Dubai. What they’ve done is phenomenal, and we’re very proud of it. But here we have a unique opportunity to get it right.”

That’s a subtle dig at Abu Dhabi’s brash neighbor to the north. On the surface, what’s happening in Abu Dhabi mirrors Dubai. But what’s driving growth here is different. Dubai is a story of survival – how one small city running out of oil saved itself with a mixture of tourism, commercialism, and pizzazz. Abu Dhabi doesn’t need to do anything. It has the oil reserves and the financial cushion to sit back and watch the Dubai experiment. But the leaders of a new generation want more. And they want it on their terms, with all the splendor and none of the crassness that has afflicted Dubai.

“They know they also have to diversify their economy away from just oil,” says Christopher Davidson, a political science professor at Durham University in Britain, who has written a book on the UAE. “But there’s also a bit of rivalry. Abu Dhabi is peeved that Dubai is internationally recognized and it isn’t.”

Khaldoon’s cellphone rings. “Hello, boss,” he says, then whispers, “When the crown prince is on the phone, you answer.”

The 46-year-old crown prince, Mohammed bin Zayed al Nahyan, has been calling a lot lately. With three dozen construction projects planned in Abu Dhabi, plus infrastructure investments in Algeria, Pakistan, and other countries, there’s plenty to talk about. “He’s like a CEO running a major corporation,” Khaldoon says. “He wants results, and he wants them now.”

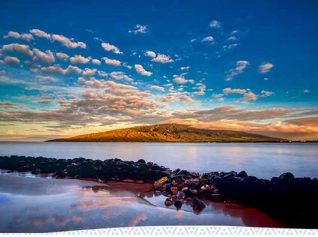

The city of Abu Dhabi sits at the tip of a T-shaped island jutting into the Persian Gulf. Wide tree-lined boulevards run through clusters of utilitarian concrete-slab high-rises and modern mirrored towers. An elegant corniche stretches the length of the city along the coast. There are finely manicured roundabouts, abundant fountains, and more trees than anywhere else on the Gulf. But it’s oddly quiet – there’s little traffic, few pedestrians, and no nightlife to speak of.

That’s all about to change. From a helicopter you can see sandy islands covered with dump trucks and crisscrossed with empty highways sitting offshore like blank canvases. It’s a stark contrast to what lies just 15 minutes up the coast by air: a landscape of cranes, yacht harbors, man-made islands in exotic formations, and what will soon be the tallest building in the world. There’s nothing subtle about Dubai. Its crowded, smoggy skyline is part Miami, part Las Vegas, and all new. There’s scarcely a plot of open space or an uncongested highway.

As much as Khaldoon and others say they don’t like to make comparisons, it’s impossible to avoid them. Abu Dhabi and Dubai operate like family businesses. While the Maktoum family of Dubai and the Nahyan family of Abu Dhabi are cousins, they were born in very different neighborhoods.

The population of Dubai, an emirate the size of Rhode Island, was concentrated in a small merchant community that capitalized on the town’s sheltered and navigable creek. Abu Dhabi, roughly the size of West Virginia, was much poorer. Bedouin tribesmen roamed the desert; pearl divers lived in huts where the city is today.

Then, in 1958, British explorers discovered what would turn out to be the world’s fifth-largest crude reserve, 90 percent of which was under Abu Dhabi. That discovery – and the wealth that came with it – made the Nahyans the dominant family in the region when the British pulled out in 1971. Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan al Nahyan, the ruler of Abu Dhabi, became President of the newly independent UAE, while Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed al Maktoum of Dubai became Prime Minister.

Zayed set out to carve a modern country in the sand. When the oil started flowing, the city of Abu Dhabi had just 46,000 people, four doctors, and five schools. Rich people had mud houses; poorer families built with reeds. “As students, we were provided with books, transportation, and a small salary,” remembers Mohammed Ahmed al Bowardi, a longtime government advisor. “Sheikh Zayed, our country’s George Washington, realized that the people needed an incentive to come to school. So that 100 dirham [about $27] meant a lot to us.”

As his country became wealthy, Zayed insisted that “not a single grain of sand” be sold. Though most men received plots of land, transferring ownership required the sheikh’s approval. As a result, native-born Arabs – rapidly becoming a minority in their own country – got land while outsiders couldn’t buy any. That made it difficult to attract foreign investment, especially when oil prices plunged to $18 a barrel in the late 1990s.

The government’s most ambitious plan at the time, the Saadiyat Free Zone Authority, an attempt to create a free-market financial and commodities center on a sandy island, never made it past the planning stage. The same fate met a proposal to build a theme park and resort on a man-made breakwater known as Al Lulu Island. One reason: Foreigners couldn’t own any land.

Dubai learned that lesson early. The emirate legalized property sales to locals in 1997 and five years later, in certain areas, to foreigners too. Wealthy Middle Easterners – including those in Abu Dhabi – accustomed to buying Italian villas and U.S. T-bills suddenly had viable investment opportunities close to home. Cash poured in, and hotels, condos, and malls sprang up. Soon Dubai was the place where Saudis shopped, Brits tanned, and Russians partied.

As Dubai raced ahead, Abu Dhabi stood still – a Melbourne to a Sydney, a Philadelphia to a New York. One businessman remembers weeds growing out of cracked streets in 2000. Zayed had grown ill, and no one dared to suggest radical changes. Another problem: Zayed technically owned all the land. “The horses were being held behind,” says al Bowardi.

That all began to change in 2004, after Zayed’s death. Power fell to two of his 19 sons: Sheikh Khalifa, his eldest, became President, and the much younger Sheikh Mohammed became crown prince, taking over the day-to-day running of Abu Dhabi. Soft-spoken but shrewd, Mohammed is considered the most Western of the emirate’s leaders. A graduate of Britain’s prestigious Sandhurst military academy, he used his control of the UAE’s armed forces to amass the economic and political clout he needed to become the heir apparent to Khalifa. (He’s also a pretty good fighter pilot.)

One of the first projects to get off the ground was Abu Dhabi’s own international carrier, Etihad Airways. The idea was to duplicate the success of Emirates, the airline that helped put Dubai on the map as a tourist destination with its high-class service. So Etihad placed an $8 billion order with Airbus, including four A380s. “It’s a function of geography,” says James Hogan, Etihad’s Australian CEO. “We’re in the middle of the world and can act as an air bridge between Europe, Asia, and the U.S.”

Three years later it’s difficult to assess Etihad’s success, since it doesn’t report earnings, but analysts doubt that two long-haul carriers can profit in such close proximity. “The idea that just anyone can put a stick in the ground and watch it grow into a tree is ludicrous,” says Richard Aboulafia, an aviation analyst at Teal Group. “There really isn’t enough traffic, not to mention that the European and Asian carriers are starting to fight back.” But if the airline’s goal is to put Abu Dhabi on the map, it’s starting to succeed – it carried three million passengers last year, more than twice the number in 2005.

The next thing Abu Dhabi needed was a landmark. The answer was the $3 billion Emirates Palace hotel, with its $1,000-a-night rooms and $10,000 suites. It was Abu Dhabi’s bid to outdo Dubai’s Burj Al Arab, the $1 billion sail-shaped hotel that has become a tourist attraction. The plan worked: While the Emirates Palace doesn’t seem to have many guests, it does have gawking European tourists.

But the most important change was Law No. 19. It formally abandoned the old property regime and permitted the sale of land by citizens and, in some areas, the purchase of 99-year leaseholds by foreigners. The real estate boom started immediately.

“Many people here had been investing heavily in Dubai,” says Ahmed Ali al Sayegh, who founded Abu Dhabi’s first private-property development company, Aldar Properties. “This was the first time they could do something in their own city.” When he took Aldar public in 2005, it was oversubscribed more than 450 times. People waited in line overnight to buy villas in Al Raha Gardens, Aldar’s first project. The $400,000 units sold out in 45 minutes.

But as much as Aldar was modeled after Emaar Properties, the development company that built much of Dubai, there wasn’t a rush to simply copy what Dubai did. After all, beneath that city’s glitter are serious problems no one likes to talk about. Its infrastructure is overtaxed, inflation is climbing, and crime and prostitution are on the rise. Abu Dhabi has a more traditional and more religious population, unwilling to sacrifice its way of life for tourist dollars.

That’s why it is building the world’s second-largest mosque. That’s why the Emirates Palace looks right out of The Arabian Nights. That’s why the city’s planned Central Market has a souk. It’s even evident in the advertising. In Dubai, property ads feature pictures of smiling, wine-drinking Westerners frolicking on the beaches. In Abu Dhabi they tend to show Arab families in traditional dress.

“We don’t seek to become a commoditized destination for mass tourism,” says Sheikh Sultan bin Tahnoon al Nahyan, chairman of the new Abu Dhabi Tourism Authority. “We’re creating an exclusive, high-end tourist destination.”

Perhaps the best example of that is Saadiyat Island, a $30 billion project that includes 29 hotels, three marinas, two golf courses, and housing for 150,000 people. But what makes it different from Dubai is the attempt to create a cultural oasis in the desert. “When we were designing it, we thought there had to be some of what we call ‘pearls,'” says Jose Sirera, an architect with Gensler, a San Francisco firm that designed the master plan for the island. “It needed art galleries or museums or special gathering places.”

By Barney Gimbel

For full article please click here

Courtesy of Fortune magazine

Chitra Mogul

Have your say Cancel reply

Subscribe/Login to Travel Mole Newsletter

Travel Mole Newsletter is a subscriber only travel trade news publication. If you are receiving this message, simply enter your email address to sign in or register if you are not. In order to display the B2B travel content that meets your business needs, we need to know who are and what are your business needs. ITR is free to our subscribers.

Phocuswright reveals the world's largest travel markets in volume in 2025

Higher departure tax and visa cost, e-arrival card: Japan unleashes the fiscal weapon against tourists

Cyclone in Sri Lanka had limited effect on tourism in contrary to media reports

Singapore to forbid entry to undesirable travelers with new no-boarding directive

Euromonitor International unveils world’s top 100 city destinations for 2025