Bali gets a culture shock

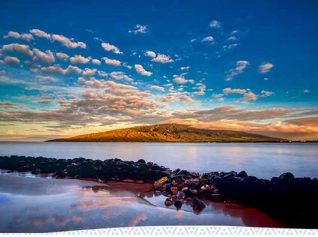

A Reuters report says that with its manicured rice terraces, Hindu temples, and processions of women bearing Carmen Miranda-like mounds of fruit on their heads, Bali has successfully sold itself as a tropical paradise.

But the island resort, which attracts supermodels and rock stars as well as thousands of less famous economic migrants in search of a better life, may become a victim of its own success.

Mosques, shopping malls, and luxury villas have mushroomed on this largely Hindu island set in the predominantly Muslim Indonesian archipelago.

If a bid to lift height restrictions on buildings goes ahead, the skyline could be set for a more controversial addition: high-rises, seen as the most effective way to deal with a growing population and rapidly shrinking supply of land.

“The religious people don’t want this, they will have a problem with the temples and the way of life,” said Putu Suasta, an environmentalist, explaining that the mostly Hindu Balinese believe that other buildings should not tower above temples.

“I don’t think they will allow it.”

Bali is being transformed by non-Balinese who some critics say are gobbling up its precious rice fields for property development, competing head-on with the Balinese for jobs, and bringing alien cultures to the island.

“I want to keep my culture,” said Luh Ketut Suryani, a psychiatrist who is lobbying to preserve and popularize Balinese ways, including language and customs, and to make it harder for other Indonesians to settle on the island.

“If you want to build a big mosque and church, build it in another place. If you don’t agree, don’t come to Bali. All Indonesians are equal but now we (Balinese) feel we are a minority.”

The proportion of Hindus in Bali fell to 87 per cent in 2000, from 93 per cent in 1995, Suryani said, as Indonesians from densely populated and mainly Muslim Java flocked to Bali in search of work following the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis.

In Bali’s capital Denpasar, the proportion of Hindus may be closer to 60 per cent and in certain districts it is only one in six, she said. The issue of Balinese versus outsiders is likely to be a hot topic in next year’s election for governor.

“Balinese only have one or two kids because family planning here is very strong” due to pressures from the local banjar, or neighborhood associations, she said.

“But imagine, if Balinese have only one or two kids but people from outside have four, five or six, in a few years the composition will change.”

Besieged by outsiders, some Balinese are becoming more aware of the need to preserve their identity.

Instead of using Indonesia’s unifying language bahasa Indonesia, which is similar to Malay, some Balinese want the Balinese language, steeped in Sanskrit and Javanese with a feudal emphasis on the caste of the person being addressed, to be used more widely.

Once famous for its warring princes and slave-trading, Bali’s potential as a tropical tourist destination was exploited by the Dutch colonial rulers and, post-independence, by the Indonesian government.

It became part of the hippie and backpacker trail, and attracted more tourists than any other part of Indonesia.

When Islamic militants blew up two bars in Kuta, a popular tourist strip, in 2002 killing more than 200 people, it dealt a severe blow to Bali’s tourist industry and put Bali’s open welcome and tolerance to the test.

“After the bombs, Balinese became aware that it’s very dangerous to receive people from outside and we don’t know who they are,” said Suryani.

But even before 2002, some Balinese had mixed feelings about tourism and development. Some complain that developers destroy local shrines or do not treat temples with sufficient respect.

The big, foreign-owned hotels and restaurants often prefer to hire other Indonesians because Balinese, who are bound by their community ties, are obliged to attend important ceremonies and events in their villages and so have to take more time off work.

And some of those who sold their land feel they were forced to give it up, or cheated of a good price.

Without their land, many have given up their farming existence and have become dependent on tourism which sometimes turn locals and their unique culture into curios.

“To compete in the tourism business is about selling themselves, their image, their creativity, they have to sell themselves as tourist objects,” said Ida Ayu Agung Mas.

As a senator, she frequently hears complaints from Balinese about the consequences of development, ranging from pollution and higher living costs to a shortage of natural building materials as more people move to the island.

“Everyone is using the image of Bali, but they must pay back to the community. The Europeans, Chinese, Javanese, they don’t give back,” she said.

A report by The Mole from Reuters

John Alwyn-Jones

Have your say Cancel reply

Subscribe/Login to Travel Mole Newsletter

Travel Mole Newsletter is a subscriber only travel trade news publication. If you are receiving this message, simply enter your email address to sign in or register if you are not. In order to display the B2B travel content that meets your business needs, we need to know who are and what are your business needs. ITR is free to our subscribers.

Phocuswright reveals the world's largest travel markets in volume in 2025

Higher departure tax and visa cost, e-arrival card: Japan unleashes the fiscal weapon against tourists

Singapore to forbid entry to undesirable travelers with new no-boarding directive

Euromonitor International unveils world’s top 100 city destinations for 2025

Cyclone in Sri Lanka had limited effect on tourism in contrary to media reports